The Bell Bottom Bulletin Checks in with Fito de la Parra of Canned Heat

Fito de la Parra on Left

Fito de la Parra on Left

When Canned Heat joins us on the Flower Power Cruise, their “endless boogie” will be in its forty-third year. Three of the earliest members (Bob Hite, Alan Wilson, and Henry Vestine, sadly all now deceased) were deep-catalog blues collectors. With or without them, the group never lost sight of the blues. Hite and Wilson loved an ultra-obscure 1928 record, “Canned Heat Blues.” (During Prohibition, a denatured alcohol heating product, Sterno’s Canned Heat, was the drink of last resort). If the name was old, the sound was new. Bassist Larry Taylor joined in 1967 and drummer Adolfo “Fito” de la Parra joined later that year, a few months after the group’s epochal appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival. They’d just recorded their first album and scored their first hit, “On the Road Again.” Heat’s on-stage reputation is so strong, they’ve recorded almost as many “live” as studio albums. We’ll get a chance to experience that in-person presence up-close when they join us on the Flower Power Cruise.

Your first gig with Canned Heat was with the Doors at Long Beach Auditorium. Who topped the bill?

The Doors. They were coming off “Light My Fire.” Top or bottom of the bill, I didn’t care. I was born in Mexico City and I hadn’t been in this country more than a year or two, and suddenly I was in one of the most popular bands around. When they asked me to join, I said, “Yes! I was born to be in Canned Heat.”

Old blues records were pretty much constrained by the length of a 78 RPM record (about three minutes). You could stretch out a song across one side of an LP (about twenty minutes).

More than that. Our third album, Living the Blues, was a double album. One of the LPs was just one song, “Refried Boogie.” In concert, it could be an hour long, but on the record it was forty minutes. We wanted to include “Refried Boogie” as a free album to go with Living the Blues, but of course the record label charged for it.

Why do you think the blues resonated with a generation that never really HAD the blues?

Hah! (laughs). The late Sixties was such an interesting time. Pop music and early British Invasion music was becoming passé. The next generation of musicians –Hendrix, Clapton, Mayall, the Rolling Stones, and so on— was heavily influenced by blues, and kids bought into it. To a lot of the black audience, it called up Uncle Tom times. But we just loved blues and dedicated our lives to playing it and getting recognition for the guys who originally made it.

Bob Hite, Henry Vestine, and Alan Wilson were big time record collectors. Did they use their royalties to go off in search of old, obscure 78s?

For a start, we never made much in royalties. We lost the recording and publishing on our songs. But Bob used every penny to buy records. If we were on the road and he’d pass an old, dilapidated house, he’d say, “I can SMELL the 78s in there.” We’d knock on the door and the people inside would freak when they saw us. Bob loved all music played with passion and he loved primitive music. Blues, bluegrass, old jazz. We all loved old jazz. Henry and I were more into R&B, like James Brown and Etta James, but we loved blues, too. Henry’s father was a big record collector. Tens of thousands of records.

Do you ever reflect on how easy it is to access that music today? Back when Bob and Alan were collecting, you had to find the original 78s. Now it’s all on YouTube.

The original records sound MUCH better than digital, but, yes, a few keystrokes and it’s all there. Unfortunately, it opened the door to musicians getting ripped off.

Bob Hite and Alan Wilson didn’t resemble teen idols, like Bobby Vee or Fabian. Does it say something about the Sixties that Canned Heat made it on music, not looks or marketability?

Yeah! Canned Heat was never a pop band. We had pop hits, but we weren’t a pop band. The hits came by accident. We wanted to play music that’s compelling. Pop artists sell their looks and their image. We were selling music.

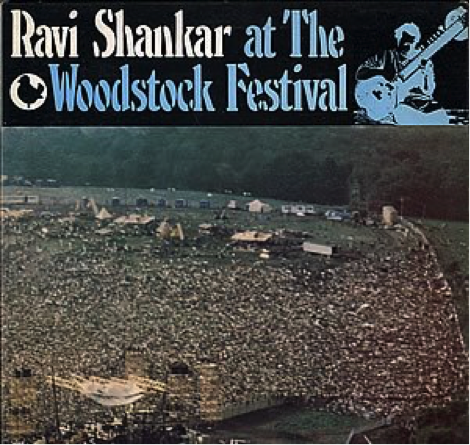

(Photo taken from Canned Heat's Manager upon the band's arrival to Woodstock)

(Photo taken from Canned Heat's Manager upon the band's arrival to Woodstock)

When you were booked for Woodstock, you probably had no idea that it would become the era’s defining moment. What did you think as you flew in to the show?

We were waiting hours and hours at a small airport, then we saw a bunch of reporters getting on a helicopter. Bob Hite said, “What are you doing?” One of them said, “We’re going to report the news.” Bob said, “Get out of the way. We’re going to MAKE news.” Remember, Bob was called “The Bear,” and his hobby was kicking in doors, like cops do. We hijacked the helicopter. If you look online at the cover of Ravi Shankar’s Live at Woodstock album, that’s what we saw when we flew in. Our road manager took that photo. Just as we flew in, we saw our roadies pulling up. Those guys had been driving since we finished the previous gig in New York the night before. They’d driven twelve hours. Roadies never get any credit, but they’re the unsung heroes. A lot of acts couldn’t get their equipment there, but our guys got our stuff there.

Why was your song “Goin’ up the Country” in the original movie when Canned Heat wasn’t?

Politics. The dark cloud over our existence. Warner Bros. did the movie and wanted as many of their artists as possible. Warner, Elektra, Atlantic artists. We were in the original cut, then edited out because they wanted the movie short enough to play four times a day in theaters. But we were restored in the director’s cut.

“Goin’ up the Country” was Woodstock’s unofficial anthem, and it still resonates. Right now it’s in a GEICO commercial. What is it about that song?

It’s pure blues. Three chords. Primitive. Primal appeal. Peace, happiness. Go to the country.

You see many kids today dressing as if they’re on their way to Woodstock. What is it about that era that still intrigues people?

Some kids are too far gone in the digital world, but some, especially young musicians, come to us and want to learn the craft of making music like we did. Learn it from the ground up. There was a lot wrong then. Vietnam, and so on. But the music was real.

Canned Heat’s founding members all died way before their time. Happily, you’re still very much among us. Do you attribute that to good luck, good habits, or…what?

I’ve learned to take care of my health. Part of it, I think, is that I’m an immigrant. I never took anything for granted. I appreciate my adventure. If you grow up with it, you can be spoiled.

There have been so many guys go through Canned Heat. Was there ever a time when the group didn’t exist?

Canned Heat has been around since 1966. There’s been tragedy, but we never stopped playing.

What prompted you to write your autobiography, “Living the Blues”?

I had a couple of friends from Mexico who moved here. We’d ride our motorcycles off up the country. They’d always say, “Tell us some Canned Heat stories.” They like the way I tell stories, and they said I should write it all down, so I did. Mike Judge, who produced Beavis and Butt-head and King of the Hill, wants to make a movie out of it.

We’re looking forward to seeing you on the Flower Power Cruise. Have you worked a cruise before?

No, and we’re all really looking forward to it.

Colin Escott © 2017